I imagine blue skies with puffy white cumulus, green grass lawns in heavens above and houses in heavens below. Neighbors walking with a smile to greet you and a shake of a hand. No wasted motion or effort. Everything with a purpose. Everything put in its place.

I don’t have a dog anymore, but even when I did have Sandy she never chased garbage trucks. She was a stray, a gypsy, a wanderer, of uncertain breed, uncertain age, uncertain origin. My dad picked her up one day at Knott’s Berry Farm in the days when the farm was still a farm and you could talk of Saturdays gone “berrying” in a purely physical, not just poetic, way. Sandy’s coat was a mix of wild oats and golden summer grass, smeared with blackberry stripes and one heckuva plum nose.

I see her riding from her summer kingdom of chasing chickarees, hounding foxes, maybe scaring up snakes, in a car up our big green hill, her strawberry sour strip tongue wagging out the window, marveling at the flick of the wind on her fur, all the posh white houses, the people walking their dogs, and maybe, if only for a moment, feeling the rush of instinct call to her in the figure of a jolly green garbage truck.

I loved her. I held her in my lap, her small body overwhelming my smaller body, her fur snugglier than any Christmas sweater than my grandma gave the winters. We chased each other round the house. (At least I chased her—maybe she was only chasing her tail.) She nuzzled me with a wet nose made warm. She barked excitedly at squirrels which tapped quizzically at their reflections on the sliding door. She raced and she stayed. She was a good, good dog.

Four years. That’s how long it took. She got slattern and senile. Left blackberries everywhere. Scatted on the kitchen floor, my bedroom, the playroom carpet. Gave the white carpet an unpleasant yellow tint, the odor of piss. Pretty much all the past years went out the window. Couldn’t stand her or the memories. Was pretty unmoved when she died.

So when I go walking in my neighborhood, now, on Thursdays, what here in the ‘hood we call our garbage days, I watch the ungainly garbage trucks trundle past with some small surprise that I’m thinking again of Sandy. The backs of them look like grenades, octagonal, with tic-tac-toe bars, and little red flashing rear-lights that signal they could explode at any moment from their fullness. A mechanical pincer goes out and clamps the black trash bin, lifting it into the air and then dumping it into the top hatch. Bits of plastic, shreds of cellophane, broken cell phones, whole soiled, tattered bedsheets feather or fly or fling themselves with gravity into the load. The truck moves on down the road and I follow, unable to escape it. I gain on it when it brakes to lift a bin, but it speeds away to the next stop just when I’m about to catch it.

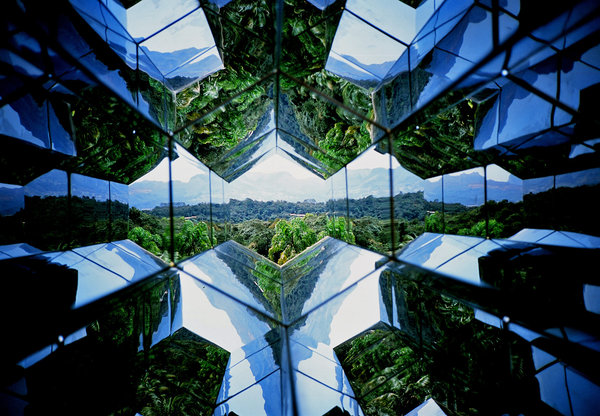

I can’t catch it. Soon enough it, or another truck, will be back again to finish the job. The black bins have been taken care of; but there are still the blue bins and the green bins. I think of the blue pills and the red pills in the Matrix: “This is your last chance. After this, there is no turning back. You take the blue pill—the story ends, you wake up in your bed and believe whatever you want to believe. You take the red pill—you stay in Wonderland and I show you how deep the Rabbit-Hole goes.”

Memory runs deep. It’s messy. Doesn’t matter if it’s created from the unchanged scraps of memory taken from the real world of your past or the memories which have metamorphosed, crystallized, ignited in the long march of Thursday garbage days.

The blue pill is the blue bin, the bin of re-iterated facts, the recycler. The fact is people still don’t know squat about recycling. Or at least can’t be bothered. Not that I can much blame them, since we’re still taught calculus in school (which, despite what your teachers told you, there is scant chance you’ll ever use), but we’re not taught the differences between a three-arrowed recycling symbol with a 1, or a 2, or a 3, or “x” in the center; what bits of formerly wanted-matter turned anti-matter should be deposited in the blue bin or the black bin. There are still some very basic things in life that blow my mind. Take fax machines. Or the Big Bang. Or how one is supposed to decide between an organic orange from Florida or a local orange grown just down the road in little paradise Sherman Oaks. The toughness of the decision doesn’t mean you shouldn’t think about it; the contemplation of the facts can even be delicious. Who knows where your mind will turn in the processing. Find progress in the pulp.

The ubiquitous cardboard box slumbers in the depths of the blue bins: simple corrugated brown boxes, Dole banana boxes, El Monte pineapple boxes, the whole shebang. Sometimes they’ve been shredded by broken glass, other times they’re good as new, still tanged with the scent of tropical fruit.

No one misunderstands the green bin. That is the earth bin. Palm fronds chopped down from gardeners shimmying up trees like they’ve spotted king coconuts, leaves raked from storm drains to prepare for the next rain, twigs and dandelions and old grass, grass that has turned golden from green.

Nature’s first green is gold,

Her hardest hue to hold,

Her early leaf’s a flower;

But only so an hour.

Then leaf subsides to leaf.

So Eden sank to grief,

So dawn goes down to day.

Nothing gold can stay. (Robert Frost)

Roses are red, violets are blue, garbage trucks are green, Sandy you’re gold too.

The garbage trucks lead me on a wild goose chase, chasing the tail of rubbish they leave behind. Step by step, I climb into its lap, dropping into the fields of gold, where Sandy lives.